Table of Contents

- 1 Question of National Language

- 2 What Gandhiji thought about English Language

- 3 Leader’s stand for Hindi Language

- 4 Two questions are being talked about in the Constituent Assembly.

- 5 Debates

- 6 Dominition of Hindi lanuage

- 7 Weakness of the Hindi protagonists

- 8 Anti Hindi movement

- 9 Outcomes of Anti Hindi Movement

- 10 Conclusion

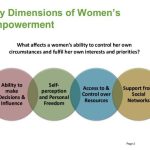

Question of National Language

• The language problem caused the most trouble when it turned into a fight against Hindi, which often led to fights between Hindi-speaking and non-Hindi-speaking parts of the country.

• The disagreement wasn’t about a national language, which is one language that all Indians would learn over time. The secular majority of the national leadership had already rejected the idea that a national language was important to Indian national identity by a large majority.

India was a country with many languages, and it had to stay that way. The different Indian regional languages were used by the Indian national movement to spread its ideas and political work.

Its desire at the time was that the mother tongue be used instead of English in higher education, government, and courts in each language area.

Jawaharlal Nehru made this clear in 1937: “Our great provincial languages… are ancient languages with a rich heritage, each spoken by many millions of people, and each tied inextricably to the life, culture, and ideas of the masses as well as the upper classes.

“It is a given that people can only learn and grow in education and culture through their own language. So, we have no choice but to put a lot of weight on the regional languages and do most of our work in them. So, our schooling and government work must be based on the languages of the provinces.

The problem of a national language was solved when the people who made India’s constitution pretty much accepted all the major languages as “languages of India” or “national languages” of India. But that wasn’t the end of the story, because the official work of the country couldn’t be done in so many languages.

There had to be one language that both the national government and the state governments could use to do their jobs and talk to each other.

The question came up: what language would be used to talk to everyone in India? Or, what would be the legal language of India? There were only two applicants for the job: English and Hindi. The Constituent Assembly had a very heated discussion about which one should be chosen.

In fact, the decision had already been made by the leaders of the national movement before India got its freedom. They were sure that English would not continue to be the language everyone spoke in a free India.

For example, Gandhiji understood the importance of English as a world language that gave Indians access to world science, culture, and modern Western ideas. However, he was also sure that a people’s genius and culture could not grow in a language that was not their own.

What Gandhiji thought about English Language

• In fact, Gandhiji emphasised in the 1920s that English is “a language of international commerce, it is the language of diplomacy, it contains many rich literary treasures, and it gives us an introduction to Western thought and culture.”

• But he said that the English held “an unnatural place” in India because our relationships with Englishmen were not equal. “English has drained the energy of the nation. It has separated them from the masses.” “The sooner educated India shakes itself free from the hypnotic spell of the foreign medium, the better for them and the people.”

• In 1946, he wrote, “I love the English language in its place, but I am an unrelenting foe of it when it takes over a place that doesn’t belong to it.

“English is, without a doubt, the language of the world today. I would give it a place as a second, alternative language because of this.’

• In his 1937 piece, “The Question of Language,” and during the debates in the Constituent Assembly, Nehru said the same things.

Leader’s stand for Hindi Language

• Hindi or Hindustani, the other language that was considered for the role of official or link language, had already filled this role during the nationalist fight, especially during the phase of mass mobilisation.

Leaders from places where Hindi wasn’t spoken accepted Hindi because it was thought to be the most widely spoken and understood language in the country.

Lokamanya Tilak, Gandhiji, C. Rajagopalachari, Subhas Bose, and Sardar Patel all strongly supported Hindi.

• The Congress used Hindi and the languages of the states instead of English in its meetings and political work.

• In 1925, Congress made a change to its constitution that said: “As much as possible, Congress business should be done in Hindustani.

“If the speaker doesn’t know Hindustani or if it’s required, he or she can use English or a provincial language instead. Meetings of the Provincial Congress Committee are usually held in the language of the province in question, but Hindustani can also be used. In 1928, the Nehru Report said that Hindistani, which could be written in either the Devanagari or Urdu scripts, would be India’s main language, but English would still be used for a while. This was based on a national agreement.

• It’s interesting that, in the end, this point of view was to be written into the constitution of free India, except that Hindustani was changed to Hindi.

Two questions are being talked about in the Constituent Assembly.

Would Hindi or Hindustani take the place of English?

How long would it take for that to happen?

Debates

• The problem of the official language was politicised from the start, so the first arguments were very different. The question of Hindi vs. Hindustani was quickly settled, but it did not end on a good note.

Gandhiji and Nehru both backed Hindustani, which is written in the Devanagari or Urdu script.

Even though many Hindi followers didn’t agree, they tended to agree with Gandhi and Nehru. But after the announcement of Partition, these supporters of Hindi felt stronger, especially since the supporters of Pakistan said that Urdu was the language of Muslims and of Pakistan.

Urdu is now seen as a sign of separation by those who speak Hindi. They said that the national language should be Hindi written in the Devanagari style. The Congress party was split down the middle by their request.

Even though Nehru and Azad pushed for Hindustani, the Congress Legislative Party voted 78 to 77 in favour of Hindi instead of Hindustani. The Hindi group also had to make a deal. It agreed that Hindi would be the official language instead of the national language.

• The question of how long it would take to switch from English to Hindi caused a split between places that spoke Hindi and those that didn’t.

Spokespeople from Hindi areas wanted to switch to Hindi right away, while those from non-Hindi areas wanted to keep English for a long time, if not forever.

In fact, they wanted things to stay the same until a future parliament chose to make Hindi the national language.

Nehru wanted Hindi to be the official language, but he also wanted English to stay as an official language as well. He wanted the change to Hindi to be slow, and he actively encouraged people to learn English because it is useful in the modern world.

Dominition of Hindi lanuage

• The main argument for Hindi was that it was the language of the largest number, but not the majority, of Indians. It was also known in the cities of most of northern India, from Bengal to Punjab, Maharashtra, and Gujarat.

Hindi’s enemies said that it wasn’t as well developed as other languages in terms of literature, science, and politics.

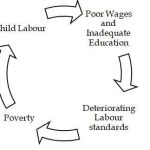

• But their biggest worry was that if Hindi became the official language, it would put non-Hindi areas, especially South India, at a disadvantage in schooling, business, and getting jobs in government and the public sector.

People who didn’t like the idea tended to say that making non-Hindi areas speak Hindi would lead to Hindi areas taking over those places’ economies, governments, societies, and cultures.

• The people who made the constitution knew that as leaders of a diverse country, they couldn’t ignore or even seem to ignore the needs of any one language group.

There was a solution, but this made some of the language rules in the constitution “complicated, ambiguous, and confusing in some ways.”

India’s constitution said that the official language would be Hindi written in the Devanagari style with international numbers. English was to be used for all formal things until 1965, when Hindi would take its place. Hindi was to be taught in several steps. After 1965, it would be the only language used in government.

But even after 1965, government would still be able to say that English could be used for certain things.

The constitution says that it is the government’s job to spread and improve Hindi. It also says that a committee and a Joint Parliamentary Committee will be set up to look at how well this is going.

The official language of the Union would be the language used to talk between the states and the Centre and between the states. However, the official language of the state would be the language used to talk between the states.

• Even though the Congress party was in power all over the country, it was very hard to carry out the language rules of the constitution. The issue was still very controversial, and it got more and more heated over time, but for a long time nobody questioned the rule that Hindi would finally be the only official language.

Weakness of the Hindi protagonists

• The people who made the constitution hoped that by 1965, the people who spoke Hindi would have fixed its problems, won the trust of people who didn’t speak Hindi, and kept their power for a longer time until they had done all of these things. It was also thought that as education grew quickly, Hindi would spread and people’s resistance to it would weaken or even go away. But, sadly, education didn’t spread fast enough to make a difference in this way.

Also, the people who wanted Hindi to be an official language hurt its chances of becoming one. Instead of taking a slow, moderate, and gradual method and relying on persuasion to get non-Hindi areas to accept Hindi, the more fanatical ones wanted Hindi to be forced on them by the government.

Their zeal and excitement usually led to a backlash. Nehru told parliament in 1959 that their overzealousness made it hard for Hindi to spread and be accepted because “the way they approach this subject often irritates others, just as it irritates me.”

Hindi was hurt by the lack of writing about social science and science. In the 1950s, for instance, there weren’t many scholarly journals written in Hindi that weren’t about literature. Hindi leaders were more interested in making Hindi the only official language than in making it useful in higher education, media, and other fields.

One of the biggest problems with the Hindi leaders was that they tried to make Hindi more like Sanskrit instead of making a simple standard language that would be widely accepted or at least popularise the colloquial Hindi that was spoken and written in Hindi areas and in many other parts of India. They did this because they wanted the language to be “pure,” without any foreign influences.

This made it harder and harder for people who didn’t speak Hindi (or even people who did speak Hindi) to understand or learn the new form. All India Radio could have done a lot to spread Hindi, but instead it made Hindi news reports sound so much like Sanskrit that many people turned off their radios when the Hindi news came on.

In 1958, Nehru, who spoke and wrote in Hindi, said that he didn’t understand the language in which his own Hindi speeches were being aired. But the people who wanted to make Hindi better did not give up, and they fought against all efforts to make news broadcasts in Hindi easier to understand. This made a lot of people who didn’t care about Hindi join those who were against it.

• However, Nehru and most other Indian leaders didn’t change their minds about making Hindi the national language. They thought that India’s official language couldn’t be English forever, even though it was good to learn English. In the interest of national unity and economic and political growth, they also realised that the full switch to Hindi should not be rushed and should wait until a better political time when the non-Hindi areas agree to it. Over time, the leaders who didn’t speak Hindi also became less open to being persuaded, and their resistance to Hindi grew. One effect of this was that people who didn’t speak Hindi stopped listening to logical reasons in favour of Hindi. Instead, they went in the direction of English that would last forever.

• In the years 1956–1960, there were sharp disagreements about the official language, which showed once again that there were tendencies to cause trouble.

• In 1956, the Report of the Official Language Commission, which had been set up by the constitution in 1955, said that Hindi should gradually replace English in different parts of the central government, with the change becoming official in 1965.

• However, Professor Suniti Kumar Chatterjee and P. Subbaroyan, who are from West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, did not agree. They said that the other members of the Commission had a bias towards Hindi and asked for English to stay. Ironically, before Bengal became independent, Professor Chatterjee was in charge of the Hindi Pracharini Sabha there.

A Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) looked over the report from the Commission. In April 1960, the President issued an order to put the Committee’s suggestions into action. The order said that after 1965, Hindi would be the main official language, but English would remain an official language as well, with no restrictions on how it could be used. After some time, Hindi would also be an option for the Union Public Service Commission exams, but for now it would only be used as a qualification. Among these were the creation of the Central Hindi Directorate, the publication of standard works in Hindi or in Hindi translation in different fields, the training of all central government employees in Hindi, and the translation of major legal texts into Hindi and encouraging the courts to use them.

All of these actions made the places and groups that didn’t speak Hindi feel suspicious and worried. Nor were the leaders of the Hindi happy.

For example, Professor Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, a famous linguist and former strong supporter and promoter of Hindi, said in his dissenting note to the Report of the Official Language Commission that the commission’s view was that “Hindi speakers are to benefit immediately and for a long time to come, if not forever.”

• In March 1958, C. Rajagopalachari, who was the former president of the Hindi Pracharini Sabha in the South, said that “Hindi is as foreign to people who don’t speak Hindi as English is to Hindi speakers.”

• On the other hand, Purshottamdas Tandon and Seth Govind Das, two of the biggest supporters of Hindi, said that the Joint Parliamentary Committee was biassed towards English.

• Many of the Hindi leaders also criticised Nehru and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, who was the Minister of Education, for taking too long to follow the constitution and for putting off replacing English on purpose. They stressed that the constitution’s deadline for switching to Hindi must be strictly followed. In 1957, Dr. Lohia’s Samyukta Socialist Party and the Jan Sangh started a movement to replace English with Hindi right away. This movement went on for almost two years.

• One way that a lot of Lohia’s fans tried to stir up trouble was by writing on English signs in stores and other places.

• The leaders of the Congress took the complaints of the non-Hindi areas seriously and handled the official language question with great care and caution because they knew how dangerous it could be for Indian politics.

• The goal was to find a middle ground. Nehru made it clear over and over that an official language could not and would not be forced on any part of the country. He also said that the speed of switching to Hindi would have to be based on what the people who didn’t speak Hindi wanted.

Leaders of the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) and the Communist Party of India (CPI) helped him do this. Hindi nationalism was criticised by PSP, which said that it “could put a lot of stress on the unity of a country with many languages like India.”

• The most important part of Nehru’s plan was a big speech he gave in parliament on August 7, 1959. He gave a clear promise to the people who didn’t know Hindi to calm their fears: “I would have English as an alternative language as long as the people want it, and I would leave the decision up to the people who didn’t know Hindi, not the Hindi-speakers.” He also said to the people of the South, “Let them not learn Hindi if they don’t want to.” On September 4, 1959, he said the same thing in parliament.

• An Official Languages Act was passed in 1963, even though it took longer than Nehru said it would because of pressure from within the party and the India-China war.

Nehru said that the goal of the Act was to get rid of a rule in the Constitution that said English couldn’t be used after a certain date, which was 1965.

But this goal wasn’t fully met because the Act didn’t spell out the guarantees in a clear way. “The English language may continue to be used in addition to Hindi,” the Act said.

The non-Hindi groups were upset that the word “may” was used instead of “shall.” In their minds, this made the Act unclear, so they did not see it as a legal promise.

Many of them wanted an ironclad guarantee, not because they didn’t believe Nehru, but because they were worried about what would happen after Nehru, especially since the pressure from the Hindi leaders was also growing.

When Nehru died in June 1964, their fears grew, and they were made even worse by some rushed steps and circulars taken by different ministries to get ready for the switch to Hindi the following year.

For example, the central government was told to communicate with the states in Hindi, but if the state didn’t speak Hindi, an English version would be added.

Lal Bahadur Shastri, who took over as prime minister after Nehru, Wasn’t sensitive enough to the views of non-Hindi groups, which is a shame. Instead of taking steps to ease their worries about Hindi becoming the only official language, he said that he was thinking about making Hindi an alternative medium in public service examinations. This would mean that non-Hindi speakers could still compete in the all-India services in English, but Hindi speakers would have the advantage of being able to use their mother tongue.

In protest, many leaders who were not Hindi changed how they were going to deal with the problem of the legal language. Before, they wanted to slow down the process of English being replaced, but now they are saying that there should be no set date for the change.

Some of the leaders went a long way beyond that. The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and C. Rajagopalachari, for example, wanted to change India’s constitution and make English the legal language.

Anti Hindi movement

As January 26, 1965, got closer, the non-Hindi areas, especially Tamil Nadu, were filled with fear. This led to a strong anti-Hindi campaign.

The DMK held the Madras State Anti-Hindi Conference on January 17. The conference called for January 26 to be a day of sadness.

• Students were the most active in organising a large-scale protest and rallying public opinion. They were worried about their careers and worried that Hindi speakers would pass them up in the all-India forces. “Hindi never, English always” is a phrase that they came up with and spread around.

They also wanted the law to be changed. Soon, the students’ anger turned into trouble all over the state. Even though the Congress controlled both the state and central governments, its leaders didn’t understand how strong the public’s feelings were or how broad the movement was. Instead of negotiating with the students, they tried to stop the movement.

In the first weeks of February, there was widespread violence and riots, which led to a lot of damage to railroads and other Union property. So strong was the feeling that Hindi should not be the official language that a number of Tamil youth, including four students, burned themselves to death to protest the policy.

C. Subramaniam and Alagesan, who were both from Tamil Nadu, left the Union government. Over sixty people died as a result of police shootings during the two months of unrest.

Indira Gandhi, who was Minister for Information and Broadcasting at the time, was the only well-known national leader who cared about the protesters. At the height of the agitation, she flew to Madras and “rushed to the storm-center of trouble.” She showed some sympathy for the agitators and became, after Nehru, the first northern leader to win the trust of the angry Tamils and the people of the South in general. • The Jan Sangh and the Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP) tried to organise a counter-agitation in the Hindi areas against English, but they didn’t get much public support.

Outcomes of Anti Hindi Movement

• Both the Madras and the Union governments, as well as the Congress party, had to change their positions because of the agitation. • They now chose to give in to the strong public mood in the South, change their policy, and agree to most of the agitators’ demands.

• The Hindi agitation ended when the Congress Working Committee announced a set of steps that would be the base for a central law that would include concessions. This led to the end of the Hindi agitation.

• The Indo-Pak war of 1965, which put an end to all disagreements in the country, caused this law to be put off.

Lai Bahadur Shastri died in January 1966, and Indira Gandhi took over as prime minister. Since she had already earned the trust of the people in the South, they were sure that she would make a real effort to end the long-running conflict.

Other good things were that the Jan Sangh toned down its anti-English fervour and that the SSP agreed to the basic parts of the deal made in 1965.

• On November 27, Indira Gandhi moved a bill to change the Official Language Act of 1963, even though the economy was bad and the Congress’s situation in parliament was getting worse after the 1967 elections.

• The Lok Sabha passed the bill on December 16, 1967, with 205 votes in favour and 41 against. The Act made it clear that Nehru’s promises from September 1959 were backed up by the law.

• It said that English could be used along with Hindi for official work at the Centre and for contact between the Centre and non-Hindi states as long as the non-Hindi states wanted it. This gave them the right to veto the issue.

The idea of being bilingual was made to last almost forever. The parliament also passed a policy decision that said the public service exams would be given in Hindi, English, and all of the regional languages. However, the candidates would need to know more Hindi or English.

In non-Hindi areas, the mother tongue, Hindi, and English or another national language were to be taught in schools. In Hindi areas, a non-Hindi language, preferably a southern language, was to be taught as a mandatory subject.

In July 1967, the Indian government took another important step on the language question. Based on the report of the Education Commission from 1966, it was agreed that Indian languages would eventually be used to teach all subjects at the university level, but that each university would decide when to make the change.

Conclusion

• After many twists and turns, a lot of discussion, several small and large protests, and many compromises, India found a solution to the very hard problem of the official and link language for the country that was accepted by most people.

Since 1967, this problem has slowly faded from the political scene. This shows that the Indian political system is able to deal with a controversial issue in a fair way that helps the country come together.

Here was a problem that made people feel very differently and could have hurt the country as a whole, but talks and compromise led to a solution that most people liked. Even though there were some bumps along the way, the Congress was able to provide good national leadership. When it came down to it, the Opposition parties also did well.

• In the end, the DMK, whose rise to power had a lot to do with the language problem, helped calm down the political situation in Tamil Nadu.

No political problem is ever really fixed for good. India is a very complicated country, so fixing problems will always be a work in progress. But it’s important that Hindi is making fast success in places where it isn’t spoken, such as education, trade, tourism, films, radio, and TV. Hindi is also becoming more of an official language, even though English is still the most common language.

• At the same time, English as a second language has been growing quickly, even in places where Hindi is spoken. This is shown by the fact that there are now private English-speaking schools all over the country, from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, even though the staff and other services aren’t very good. The quality of spoken and writing English has gone down, but the number of people who know English has grown by a lot.

Both English and Hindi are likely to become more important as link languages, while regional languages are becoming more common in government, educational, and media settings. The fast rise of newspapers in Hindi, English, and regional languages shows that these languages are getting more popular.

• In fact, English is not only likely to last forever in India, but it is also likely to grow as a language used by the intelligentsia all over the country, as a language used in libraries, and as a second language in universities.

Hindi, on the other hand, hasn’t done any of these three things yet. The goal of making Hindi the link language of the country is still there, of course. But the way that Hindi’s eager supporters fought for Hindi’s cause made it less likely that this would happen for a long time.